Women’s history month makes me reflect on the significance of personal history. The “history” we study in school is crucial, of course; it contains the story of the world we share, the people and events that have shaped our era. But history would not have come alive for me as a student without the personal stories I collected from family.

In “The Granddaughter Necklace,” I include a story my grandmother Mildred told me. She said that when she was six-years-old, her family gave her away to relatives. My grandmother was one of thirteen children. Her father was a traveling wallpaper hanger during an era when careers for African Americans were severely curtailed because of racism. My grandmother’s mother was the daughter of a middle class couple, but with thirteen children to feed and a husband who had to travel for employment, my great-grandmother was overwhelmed. So she gave my grandmother away to a relative who had only one daughter. My grandmother’s life was not a happy one in the new home she was sent to. That’s something I left out of “The Granddaughter Necklace.” The relative who became her guardian treated her like a servant. She desperately wanted to escape but she was only a child. She finally managed to leave when she was a teenager, but holding down a job to support herself meant she had to drop out of high school.

It wasn’t until I was nearly grown and about to leave home for college that I learned how unhappy my grandmother’s early years had been. Letting on to me that her family had been so poor was an act of trust on the part of my proud grandmother. But that trust drew us closer. I admired her even more. She’d survived her difficult childhood. She wasn’t bitter. She’d worked hard to make sure that her own family would have the comfort of home she’d missed when she was growing up.

In 1911, the year my grandmother was born, a terrible fire took the lives of women and girls in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York City. Most of these women were immigrants, working for low wages in unsafe conditions. Yet, 1911 was also the year the grand ocean liner the Titanic was launched to great fanfare. It was also the year Marie Curie, a Polish woman with French citizenship, won the Nobel Prize in chemistry.

Women in the United States wouldn’t have the right to vote until 1920 when my grandmother was nineteen and the Nineteenth Amendment was added to the Constitution. It wasn’t until 1964, that the Civil Rights Act, prohibiting job discrimination on the basis of sex and race, was passed. By then my grandmother was fifty-three. She was destined to live almost her whole life without protection under the law from discrimination. I ask myself how my grandmother’s life might have been different if she’d been born in a later generation. Yet her legacy is one of hard work and optimism, generosity and cheerfulness. When I was in high school, she went back to school to get her own delayed diploma. She was with me when I graduated from college. I was with her when she retired from her government job. When I think of “women’s history,” I think of my grandmother, and the memory of her life makes the world she was born into come alive.

My grandmother, Mildred Lewis

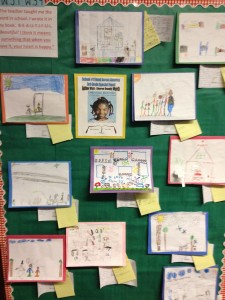

To celebrate Women’s History Month this year, I paid a visit to my local library in Montclair, where I participated in a program honoring the theme of my picture book “Something Beautiful.” Mrs. Sandra McKnight, a veteran educator and literacy expert, conducted the first half of the program, inviting kids, their parents and grandparents to write about the “something beautiful” in their lives. After the writing portion, those in attendance were invited to create “beautiful” constructions using an array of recycled materials. The creative and harmonious atmosphere in the room was inspiring and so was the writing and artwork.

To celebrate Women’s History Month this year, I paid a visit to my local library in Montclair, where I participated in a program honoring the theme of my picture book “Something Beautiful.” Mrs. Sandra McKnight, a veteran educator and literacy expert, conducted the first half of the program, inviting kids, their parents and grandparents to write about the “something beautiful” in their lives. After the writing portion, those in attendance were invited to create “beautiful” constructions using an array of recycled materials. The creative and harmonious atmosphere in the room was inspiring and so was the writing and artwork.